About DadPad, Key Content, Neonatal

About DadPad: How the DadPad Neonatal complements the FICare Model

Posted on 16th May 2023

Since its launch back in 2018, the DadPad Neonatal has been helping neonatal units across England get new dads more included, engaged with and supported as they get to grips with their family situation and their immediate surroundings. Co-designed and developed by Prof Minesh Khashu – Consultant Neonatologist at Poole Hospital and Professor of Perinatal Health at Bournemouth University – and the team at DadPad, together with other experienced neonatal professionals and ‘real-life’ neonatal dads, the DPNN was Highly Commended in the Innovation category at the BMA Patient Information Awards in 2019. With the introduction of the FICare Model to neonatal care, we’re excited to be able to share with you the ways in which we think the DPNN is a fantastic ‘fit’ to help Neonatal Units achieve true equity and equality in working with neonatal parents in partnership.

What does the DadPad Neonatal cover?

The book has been specifically designed to be used as a ‘quick start’ guide, covering dads’ most immediate concerns, such as:

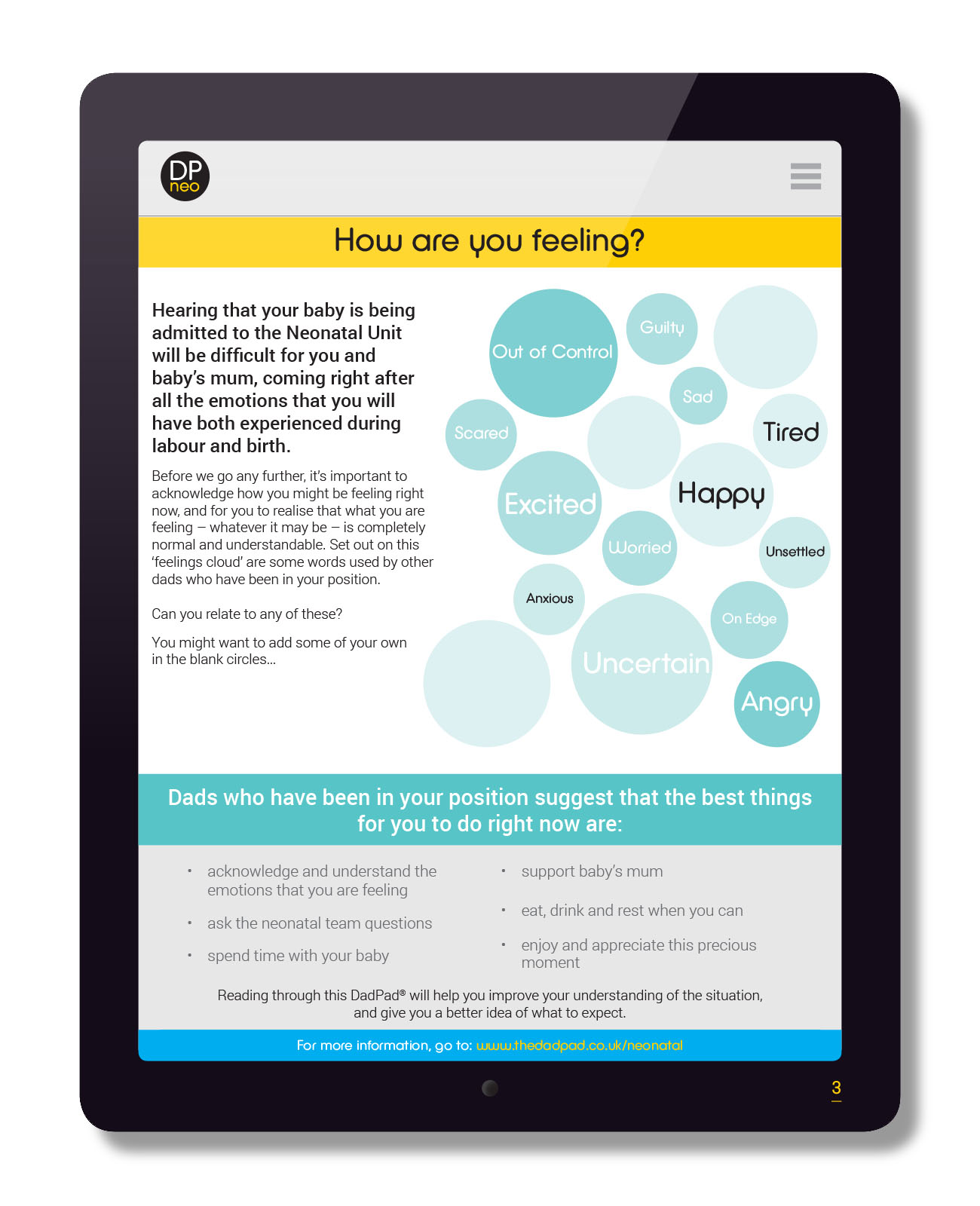

- How are you feeling?

- What is the neonatal unit?

- Why has my baby been admitted to the neonatal unit?

- What level of care is my baby receiving?

- The first few days

- Some common first questions

From here, the DPNN changes into a more in-depth guide, covering things like equipment, who is looking after your baby, developmental care, baby’s development, how you can get involved with the day-to-day care of your baby, and multiple births.

What is FICare?

The FICare – or Family Integrated Care – model of neonatal care aims to promote “a culture of partnership between families and staff; enabling and empowering parents to become confident, knowledgeable and independent primary caregivers” to their babies. Neonatal unit which embrace this approach will “nurture families into this role by listening to them, building on their strengths and encouraging their participation in experiences and decision-making to enhance control and independence… (ensuring) that they can be family as soon as possible; creating space for necessary medical care whilst facilitating the nurturing bond and love that only they can provide for their baby” (BAPM (2021) p5).

Based on extensive research, existing protocols – such as the Family Centred Care model and the Bliss Baby Charter – and a pilot study developed by a team of medical professionals at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, the ideas and thinking behind the idea are summarised by Dr Shoo Lee, Principal Investigator, Family Integrated Care at the hospital in this short YouTube video:

This key paragraph from Dr Lee’s talk summarises some of the key benefits to be gained from adopted the FICare approach:

…families have a very important part to play in the care of the baby and they do that through participation in many things, in providing the care itself, in providing insights into how the baby is doing because they are the ones who are closest to the baby on a daily basis and know the baby really well, by discussing with the doctors and nurses how best to care for their baby. And also, by involving themselves, they are contributing not only to the welfare of the baby but actually also enhancing their own health, because the family is also affected by the baby’s illness. It also gives the doctors and nurses a very different perspective of how to interact with the families and how to care for the entire family, as opposed to just caring for the baby, so it’s a big shift in thinking.

There are five key principles of FICare, as set out in the BAPM (2021) Family Integrated Care: A BAPM Framework for Practice publication:

- Partnership with families: families are seen as equal partners in the care team, and integrated into all aspects of their babies’ neonatal journey, including shared decision making;

- Empowerment: families are provided with education, training and support to have the confidence, knowledge and tools to understand and engage fully in their babies’ care and to advocate for their needs;

- Wellbeing: family mental health and welfare are priorities, with access to support and information that promote and enable wellbeing, including specialist psychological care, peer support and education. Staff wellbeing is prioritised with a focus on positive workplaces, psychological support to prevent burn-out, and improved collaborative team working;

- Culture: neonatal units are underpinned by a shared and collaborative culture that promotes the integration of families into the delivery of care. Staff are empowered to lead the implementation of FICare, to support families and to enjoy positive partnerships with them;

- Environment: neonatal units provide physical and social environments that are family friendly, comfortable and which enable parents to spend as much time as they wish with their babies, minimising separation and enhancing experiences of care.

We’ll look, a little later on this blog post, at the ways in which the DPNN can help neonatal teams achieve these principles but, before we do that, it’s important to recognise that, even though this is a fantastic initiative, ensuring that it is applied in an equal and equitable way to BOTH of baby’s parents might be a little more challenging than perhaps first appears…

Image taken from p4 of BAPM (2021)

What are the barriers to dad-involvement in the neonatal unit?

For the past 10+ years, we’ve been working on providing resources which enable dads to become better involved and engaged with in the perinatal period – from Day 1 of pregnancy, through to baby’s first birthday (and beyond). We’ve learnt during this time that there is an incredibly strong case for dads needing specific resources and support services to enable them to achieve this.

During our time working in the perinatally-focused ‘dad-sphere’, it’s become increasingly clear to us that there are, at present, too many barriers in place which make it harder for dad to take an equal role as expectant and new parent, alongside baby’s mum, even though reports and initiatives – such as the 2003 Every Child Matters report and the 2019 First 1000 days of life report – have advocated for broader involvement of ALL family members in maternity and connected services.

These barriers include historic and ingrained perceptions of the ‘expected’ gender-focused roles to be played by each parent, which are often upheld and sustained (whether intentionally or not) by extended family, friends and even the healthcare professionals supporting the family.

In addition to this, we know that dads have reported feeling excluded by and from maternity services. A report from the Fatherhood Institute in 2018 identified, for example, that – even though NHS policy requires there to be ‘family-centred’ maternity care – “there is no evidence of systematic implementation of these policies, nor of any monitoring or evaluation” (p6). Their research found that maternity services didn’t ask:

- 82% of dads-to-be/new dads about their mental health

- 78% about their physical health

- 65% about their roles

- 48% about smoking…

- …and 56% weren’t called by their name.

This is all despite the fact that:

- 100% of fathers are present at conception;

- 99% are present at an ultrasound scan;

- 94% attend at least one routine antenatal appointment; and

- 98% attend at some point during labour and birth, with 91% there from start to finish.

Research from Baldwin et al (2018) found that: “Men were often not viewed or treated as equal partners and lacked acknowledgement or involvement by health professionals during their transition to fatherhood” (p2120).

Added to this, most of the resources, information and facilities in place to assist new parents are mum-centric. Even within those leaflets, resources or websites purportedly written for ‘parents’ rather than ‘mums’, it usually doesn’t take long to find the obvious clues that the writers didn’t really have dads in mind when they wrote their materials, with phrases like ‘when you give birth’ or ‘when you are breastfeeding’ often creeping in. And, even where dad is explicitly acknowledged, his role is often viewed as being secondary: be alert to wording which suggests ways in which dad can ‘help mum with baby’, with the clear implication that mum is the one taking the lead in this role, and dad is a mere underling…

This lack of appropriate, dad-focused resources is recognised in academic research, including Baldwin et al’s (2018) observation that: “The main barriers to new fathers accessing or receiving adequate support were related to the lack of resources aimed specifically at men“, and the Fatherhood Institute’s (2018) recommendation that:

Pre-natal health education and information should be directed at men as well as women, and maternity services should be required to provide information directly to the father/woman’s partner, rather than relying on the ‘woman as educator’.

A quote we use often is this one, below, from Jeszemma Garratt, Head of Training at the Fatherhood Institute, who told us:

One of the points we stress in our work is the importance of using the ‘F’ word (father) in any letters, posters, papers, briefings, tender documents or other communications you produce. Unless you explicitly address fathers, they are overlooked and implicitly excluded: most people (mothers and fathers, practitioners, policymakers, researchers, etc) see word ‘parents’ and read it (consciously or subconsciously) as meaning ‘mothers’. This is important because it helps create a situation where dads (by which we mean the full diversity of men with a significant caring role in children’s lives, including biological and other fathers and father-figures), as well as mums (in a similarly diverse sense), feel comfortable and valued – in the context of a culture which still privileges women as more naturally suited to caring, and more important as parents (and, by extension, less important in other contexts, e.g. the workplace).

So, although the concept of Family-Integrated Care is a relatively new – and positive – one, we can already speculate from existing research studies that there is a risk that dads may:

- be inadvertently (or maybe even purposely) missed or overlooked by the healthcare professionals supporting baby, in favour of mum, seeing her as the primary caregiver;

- not feel as included as they should be;

- believe that they are inadvertently stepping into ‘female only’ territory; and/or

- not find themselves expressly referenced in the information and materials provided to them by the Unit.

[It’s interesting to note that, within the BAPM Framework document itself, whilst there are a few pictures of dads and/or dad-and-mum with baby included, the dominant gender shown in the imagery is female. On pp27-31, for example, where ‘Real Examples of FICare’ have been included, the three group shots show somewhere in the region of 27 women in total, and just 3-4 men. And a search of the text shows that the word ‘dad’ or ‘father’ (or versions of the same) do not appear anywhere. Admittedly, the word ‘mum’ or ‘mother’ doesn’t appear, either – but the use of the words ‘parent(s)’ and ‘families’ will – we know from the research, as stated above – more likely than not be read and ‘seen’ as predominantly referencing the mother].

Added to this, it’s an established fact that the mental health of dads – just as much as mums – is at real risk during the perinatal period, for a whole host of reasons including, but not limited to, hormonal changes, lifestyle changes, financial pressures, stress and anxiety, lack of sleep and having potentially been a helpless and passive witness to some traumatic events. Barriers here, preventing dads from getting the support, understanding and care that they might need, again include outdated views around how men are expected to behave, emotionally, and a lack of specialist support services. These risk factors are potentially even higher in relation to dads with a baby in the neonatal unit. Back in 2018, Prof Khashu commented:

In neonatal care, we don’t think enough about the stress dads are under. They can be separated from their family for a long time. There is a lot of bravado and men are not always good at showing emotion.

We talk a lot about postnatal blues for mum, but not for dads – and having a baby in neonatal care is even more stressful than normal. They can be in there for months.

How can the DadPad Neonatal help?

Right from the start of developing the DPNN, the idea of family-integrated care has been central:

…we’ve had a clear focus on the need to support dads in honestly and openly acknowledging the range of emotions that they may be experiencing, rather than putting pressure on them to shut down their true feelings in order to ‘be strong’ for baby’s mum.

…we’ve emphasised to dads that they are a hugely important person in their baby’s life – even if that baby is in an incubator and attached to various machines and equipment via tubes and lines. The ‘gift’ of their own DadPad Neonatal upon arrival at the Neonatal Unit might just, for a split second, help them feel valued, ‘seen’ and congratulated on having recently become a new dad.

…we’ve set out to dads the ways in which they can start to get involved with baby’s care from the very beginning, normalising with them that expectation of participation, and linking this connection with matters of longer-term significance, including the establishment of the all-important bond between dad and child.

…we’ve also raised with dads the expectation of being purposely and regularly engaged with by the healthcare team supporting their baby, by making the DPNN an interactive resource where dads can record the information that is being shared with them. We’ve also included sections where dad can note down the questions he might have, so he doesn’t forget them when he gets the opportunity to speak with one of the team.

…and we’ve included a whole host of sections of ‘further reading’, aimed at enabling dad to become more knowledgeable and more familiar with the words, phrases and terminology being regularly used in the unit, which will empower him to feel more ‘equal’ in that setting.

So, how do these points equate with the detailed aims of the FICare Model?

Partnership with Families on Neonatal Units (BAPM (2021), p13):

- Positive, mutually respectful partnerships are established between staff and families, with families support to become involved in their babies’ care as primary caregivers;

- From admission (or before, in high-risk pregnancies anticipated to result in neonatal admission), families are supported and encouraged to be comfortable providing care for their babies;

- Families are supported to be actively involved in daily rounds, daily care planning and decision-making;

- Families have opportunities to give feedback about their babies’ care while on the unit and after discharge;

- Families’ experiences and feedback are actively sought, to inform and improve the quality of services;

- Technology and innovations are used to support family participation in care; and

- Local FICare steering groups, comprising families, parent advisory groups and members of the multidisciplinary team, are established to drive improvement.

Using the DPNN within a Neonatal Unit promotes the idea – right from the very start – that parents, and dads in particular, are seen as equal partners in the care of the baby. The resource encourages regular interaction and communication, the asking of questions and sharing of knowledge and information between parents and team members. Information is included which provides suggestions on how dad can start to become hands-on in the care of his baby. Future ambitions – with the development of the forthcoming DPNN app – will include the provision of online community groups within which dads can share their experiences with others in the same position and also seek support from the neonatal team.

Empowerment on Neonatal Units (BAPM (2021), p14):

- Families are orientated to the neonatal unit before (if admission anticipated) or on admission;

- Families have access to information which outlines their role as caregivers and the philosophy of an integrated approach to delivering neonatal care;

- Ongoing orientation to support services available to families during their stay, including engagement with local charities and third sector organisations;

- Provision of a structured education program for families;

- Ongoing individual skills teaching and support for families at the cot side;

- Family classes and activities offered at convenient times, including out-of-hours, evenings and weekends; and

- Opportunities actively created for peer-to-peer learning.

The DPNN provides information directly to dads which outlines their role as caregivers, and which also includes a range of information which dad can use to really start getting to grips with better understanding the terminology and equipment used within the Unit, all of which will help to empower him as a primary caregiver in his own right.

Wellbeing on Neonatal Units (BAPM (2021), p14):

- Families and staff have access to specialist psychological and mental health support on the unit and after discharge

- Regular unit and community-based opportunities for peer-to-peer support/family group activities;

- Consideration of the use of family liaison officers;

- Pro-active use of appropriate translation services and written literature in different languages to mitigate the impact of language barriers;

- Inclusive and equitable access for all families;

- Clear processes for ensuring consistent family access when transferring between units;

- Wellbeing activities are offered to all families (e.g. yoga, crafting, meditation) and staff; and

- Engagement with local charities, third sector organisations and community groups providing wellbeing support for families.

A clear focus on dads’ emotional response to the situation that he finds himself in is front-and-centre in the DPNN. One of the first things that the resource asks him to do is to reflect on how he is feeling, with prompts share to encourage him to reflect, but also to recognise that he may well be experiencing a whole range of emotions, all of which are completely natural and none of which are ‘wrong’. Later in the resource, there’s further information on ways in which he can look after his own wellbeing at the time (including information on national support services) as well as that of his baby’s mum.

Culture on Neonatal Units (BAPM (2021), p15):

- Education and training activities for all neonatal team members on the philosophy and benefits of FICare and the expectations of their practice to support families;

- FICare education and training include in staff orientation and annual skills updates;

- Staff training in communication, coaching and mentoring skills;

- Training for staff in the provision of developmentally-supportive care, neurodevelopmental care and trauma-informed care;

- Identification of multidisciplinary FICare champions to support changes in practice; and

- Engagement with families in all aspects of the development and delivery of neonatal care locally.

Having the DPNN as an integrated part of the FICare culture in a Neonatal Unit ensures that engagement and interaction with baby’s dad becomes an ingrained, established and automatic part of the admission process, and beyond. Ensuring that each dad receives his own copy of the DPNN, addressed to and written specifically for him and his needs as a new dad, will ensure that no one is forgotten or overlooked, and each dad is empowered to start conversations, seek information and ask questions.

Environment on Neonatal Units (BAPM (2021), p15):

- A welcoming and shared neonatal unit environment including a dedicated family rest room, kitchen facilities for heating and storing food, and personal storage space;

- 24-hour open access for families to be with their babies, including during ward rounds and nursing handovers;

- A comfortable cot-side environment, with access to reclining chairs, breast pumps and screens for privacy;

- A dedicated room for mothers to express breast milk in comfort and, if preferred, privacy;

- Pro-active signposting of financial support for families, including for travel costs, food and parking;

- Pathways to ensure streamlined and consistent transition of care when babies and their families are transferred within and between units;

- Availability of on-site childcare/play therapists to support siblings;

- Access to dedicated neonatal family accommodation for all those who need it;

- Rooming-in facilities for families to aid transition to home discharge; and

- Dedicated rooms for families to stay with their baby during end-of-life care.

As we move towards the development of the DPNN app in 2023-24, each individual Neonatal Unit will have the opportunity to include bespoke information for their families on the resources and facilities available to them, both within the Unit and in the wider community. This could include signposting of local and national support services deemed relevant to neonatal families, as well as links to wider parent-focused resources within the DadPad app itself.

To find out more…

For more information on the DadPad Neonatal, and how you could acquire this resource for your Unit, please message Julian via our contact page or phone him on 07403 274757.

References and further reading:

British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) (2021) Family Integrated Care: A Framework for Practice (2021) (online)

Evans, Nick (2018) ‘DadPad guide aims to help fathers adjust to caring for their baby in a neonatal unit’, in Nursing Children & Young People (online)

Family Integrated Care website

DadPad blog posts, looking in more detail at the barriers to and importance of dad-involvement throughout the perinatal period and beyond:

- Why dads?

- DadPad as a feminist concept

- Why dads’ mental health matters

- Equity in parenting

- How do I support my child’s emotional growth?

- Infant Mental Health and the importance of secure attachment

DadPad blog posts, looking in more detail at aspects of dads’ perinatal mental health: