Ask DadPad, Mental Health

Ask DadPad: Why suicide prevention matters for dads

Posted on 10th September 2021

TRIGGER WARNING:

Suicide, PTSD, Birth Trauma, Depression

Today – 10th September 2021 – marks the one-year anniversary of the visit to London by a group of self-proclaimed ‘dadvocates’ (DadPad’s Julian being one of them) to present a report setting out 10-years’ worth of findings on the importance of fathers’ mental health during the perinatal period. Written by Mark Williams and sponsored by DadPad, the report was handed in at Westminster, via Chris Elmore MP, and to the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), along with social media support across the day in order to raise the issue that dads need and deserve equality of care during the perinatal period.

Photo from Helen Birch, showing the team (many of whom are now part of the newly-formed PMHA) delivering copies of Mark Williams’ Fathers’ Reaching Out Report to the NICE Headquarters in September 2020.

Mark had picked the date of 10th September to publish and present his report because it is World Suicide Prevention Day, and the link between men, fathers and suicide cannot be ignored. For example:

- fathers with perinatal mental health problems have been found to be up to 47 times more likely to be rated as a suicide risk than at any other time in their lives (Quevedo et al, 2011);

- the World Health Organisation estimated that, globally, over 703,000 people die from suicide in 2019 – which amounts to one person every 40 seconds. With suicide rates 2.3 times higher in men than women, this means that there is the equivalent of one male death by suicide per minute; and

- over 39% of new fathers were found to want support for their mental health (Mental Health Foundation, 2018).

Suicide statistics

These figures are supported by statistics published by the International Association for Suicide Prevention in relation to this year’s World Suicide Prevention Day, including that:

- an estimated 703,000 people died by suicide worldwide each year;

- the global suicide rate is over twice as high among men than women; and

- an individual suffering with depression is twenty times more likely to die by suicide than someone without the disorder.

The latest provisional data for the UK – released this week by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) – show that there were 10.4 suicide deaths per 100,000 people in each of the two quarters of 2021, with male suicide deaths for Q1 being 15.4 per 100,000 people and for Q2 being 15.5 per 100,000 people. These figures are three times as high as those for women, where the rate was 5.7 and 5.5 suicide deaths per 100,000 in Q1 and Q2 respectively.

These figures are similar to those released this time last year in relation to 2019, although the rate for men has (thankfully) dropped slightly from its two-decade high of 16.9 suicide deaths per 100,000.

Although we don’t have age-specific statistics available to consider from the ONS yet, we know that – in 2019 – men aged 45-49 were at the highest risk of suicide and increased rates of suicide continued in the 25-44 year age group.

What about dads?

Hopefully, given the gender and age profile of those most at risk of death from suicide, the link to the need for better mental health support for dads is obvious. Further, studies (such as those by Quevedo et al (2011) and Knapman (2018)) have identified that the risk of suicide during the postnatal period for fathers is almost 5%.

As mentioned above, those experiencing depression are at higher risk of suicide than those without the condition and it is now well-established that – like new mums – fathers and partners can be affected by postnatal depression (or PND). Dr Andy Mayers, academic psychologist at Bournemouth University, explains:

Often, the perception is that dads cannot get PND because it’s hormonal. As it happens, hormones play a very small part in the risk for maternal PND. Environmental factors (such as income, housing, partner support, the mother not having her own mother close by, education, etc) and psychological ones (previous mental health, coping skills, etc) play a much larger part in maternal PND.

As new dads will be impacted by these environmental and psychological factors in the same way as new mums, along with situational changes (such as lack of sleep, added responsibility, increased worry about all sorts of things, dealing with relationships with the wider family and friends, etc) AND also experience hormonal changes around the time of the birth (more nuanced than with mum, but the fluctuations still happen, with testosterone levels dropping and oestrogen levels rising), it’s no surprise that PND is a non-gender-specific condition. The latest figures indicate that, similar to mums, somewhere in the region of 10% of all new dads are known to suffer PND.

Even if dad doesn’t experience PND, there are a whole host of other mental health conditions which can arise – and/or be exacerbated – around the time of birth, including (definitions from Dr Jane Hanley, from Perinatal Mental Health Training CIC):

- PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder – an anxiety disorder usually caused by experiencing a frightening, distressing or terrifying event over which the father has no control, with fathers at especial risk where a pregnancy, labour and/or birth has been particularly traumatic; and

- Paternal Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) – a more-recently recognised condition where fathers experience intrusive thoughts which concentrate around harming their baby, and which lead to fathers avoiding situations where they might cause harm, in order to prevent them from acting out their thoughts.

There are also, of course, fathers with both known and undiagnosed mental health disorders, such as Bi-Polar Disorder, Antisocial Disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) and PTSD from previous life experiences.

Helping those around us

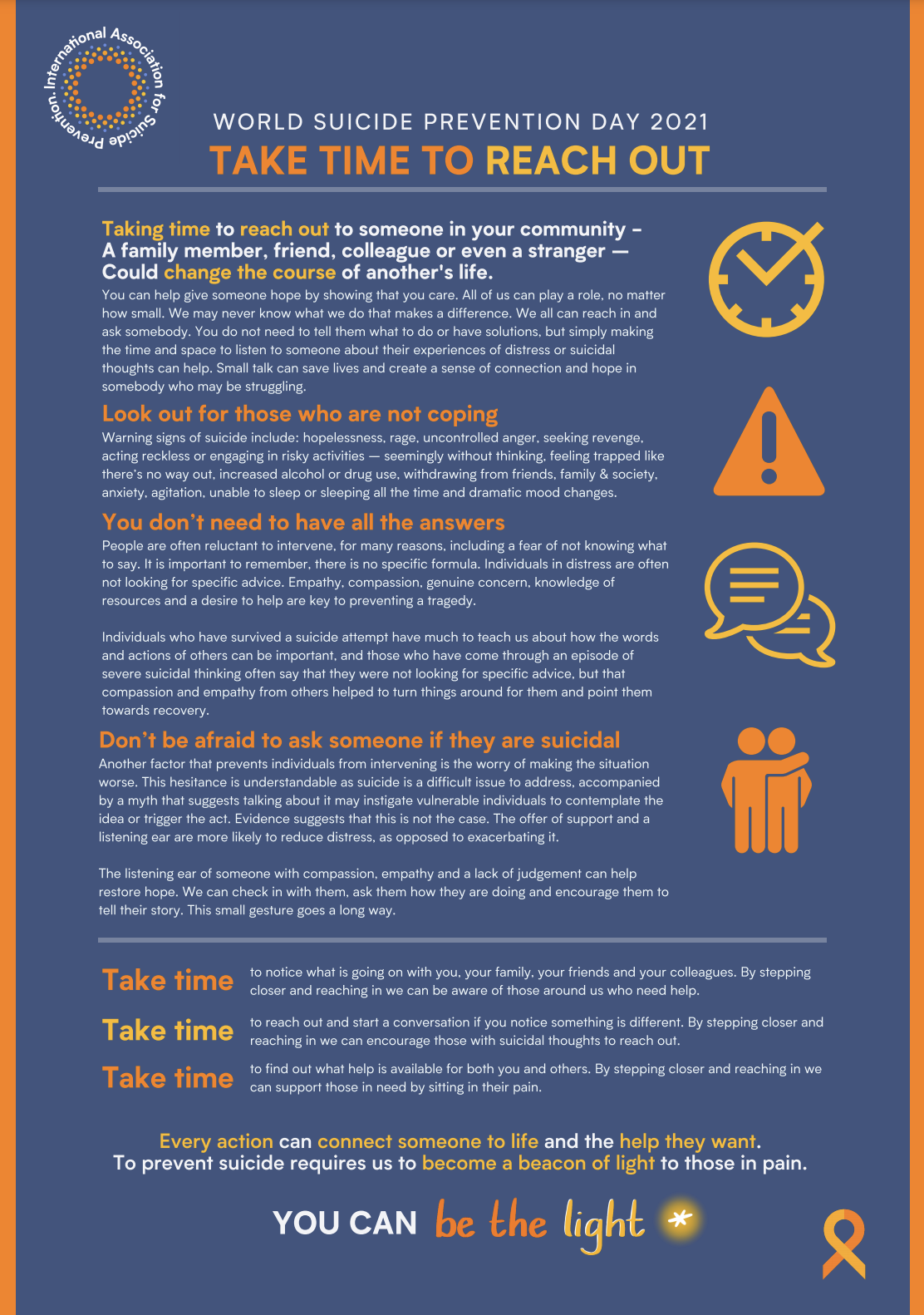

One of the biggest worries for those of us close to a person who we fear may be or know to be depressed and/or contemplating suicide is what to do to help them. The IASP have, though, offered some brilliant advice which can be downloaded in full from their website (picture below), with key points including:

- Take time to reach out – you can give someone hope by showing that you care.

- Look out for those who are not coping – warning signs of suicide include: hopelessness, rage, uncontrolled anger, seeking revenge, acting recklessly or engaging in risky activities, feeling trapped, increased alcohol or drug use, withdrawing from friends, family and society, anxiety, agitation, unable to sleep or sleeping all the time, and dramatic mood changes.

- You don’t need to have all the answers – you do not need to tell them what to do or have solutions, but simply making the time and space to listen to someone talk about their experiences of distress or suicidal thoughts can help. Those who have survived a suicide attempt often say that they were not looking for specific advice, but that compassion and empathy from others helping to turn things around for them and point them towards recovery.

- Don’t be afraid to ask someone if they are suicidal – obviously, many of us worry that we might make the situation worse by attempting to speak with someone who is contemplating suicide. However, the evidence suggests that the offer of support and a listening ear are more likely to reduce, rather than exacerbate, the distress that an individual is experiencing.

Further help for those with – or close to those experiencing – suicidal thoughts can be found on websites such as the NHS’s Help for suicidal thoughts, the Samaritans’ advice page on How to support someone you’re worried about and the Rethink Mental Illness page for those dealing with suicidal thoughts.

The current position

The good news is that the NHS Long-Term Plan from 2019 has introduced the commitment to offer:

… fathers/partners of women accessing specialist perinatal mental health services and maternity outreach clinics evidence-based assessment for their mental health and signposting to support as required.

However, although these changes need to be celebrated as having come about as a result of many years of campaigning by those involved in the paternal perinatal mental ill health field, and they will help many, many men who – previously – would have been left to flounder, there is still much more to do to ensure that new dads are fully supported. Dr Andy Mayers has identified two specific difficulties with the Long-Term Plan’s proposals, including that:

- Only the most acutely unwell mums will be referred to perinatal mental health services and therefore only a limited number of partners will be offered support. Partners of women whose perinatal mental ill health is insufficiently severe to meet the referral criteria will remain without support; and

- Fathers and partners can, of course, develop perinatal mental health difficulties independently of their wife/partner, and these dads are also excluded from the offer.

Further, three research papers that Dr Andy Mayers has contributed to over the past 12 months – all relating to aspects of paternal mental health – repeat ongoing issues, including:

- that fathers seem reluctant to seek support for their own mental health during the perinatal period, perceiving that perinatal health professionals view “mothers as the priority”. This, and the limited support that is available for dads needs to be addressed; health professionals also need more training on how to recognise that fathers are also important and need support for their mental health [1];

- that there is an overall lack of support for many fathers, despite many wanting support on how to help their partner, information on their own mental health and the services available. Fathers specifically wanted healthcare professionals to sign-post them to someone they can talk to for emotional support, and to be taught coping strategies which would help them to support both their partner and baby [2]; and

- fathers reported that witnessing their partner’s traumatic birth had a significant impact on them which they felt affected their mental health and relationships long into the postnatal period. However, there is no nationally recognised support in place for fathers to use as a result of their experiences, with participants in the study attributing this to being perceived as less important than women in the postnatal period, and maternity services’ perceptions of the father more generally. Support therefore needs to be available for both the mother and the father, following a traumatic birth, with additional staff training geared towards the father’s role [3].

We also spoke, this week, to Kieran Anders from Dad Matters UK for an update on how the Long-Term Plan’s recommendations are being implemented in practice. He told us that the intention had been for the assessments to be rolled out in 2021, but – due to Covid – this has obviously been delayed.

Despite this, Kieran is upbeat, with research having taken place into key issues such as the screening tool(s) to use (the most-common existing tool – the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – had only previously been validated for use with mums), how those tools are to be used in practice, and who will be responsible for the screening, alongside making sure that all screening has the potential to lead into pathways of support and other services for those dads who are identified as needing additional help.

Other challenges include considering where the screening information will be stored, and ensuring that the pathway that is put in place is robust, useful and does not simply pay lip service to the idea of supporting dads’ perinatal mental health.

This, together with other initiatives such as The Best Start for Life early years review and the maternal mental health services pilot areas, all means that the support available for new dads experiencing mental health difficulties during the perinatal period is definitely improving, which is great news – but much, much more still remains to be done.

What next?

Obviously, until the screening, support, and treatment for dads during the perinatal mental health period is thorough and all-encompassing, our job is not done. It’s important to therefore keep campaigning for change, to keep raising awareness of male mental health issues (reducing stigma is one of the biggest battles), and to keep providing information on all aspects of perinatal mental ill-health, including what to look for and where to go for help. There’s further information on all these topics and more via some of our previous blog posts, including information on how to best support your own and your partner’s perinatal mental health, PND in dads, why dads’ mental health matters and where to go to access support for your mental health.

You can also find out more about the work of the newly-formed Paternal Mental Health Alliance, who are campaigning for change in this area, via their Twitter account (@MentalPmha) and via our interview with founding member Helen Birch.

We’ll end with this quote from Helen, who lost her partner to suicide when she was 8 weeks’ pregnant. The couple had previously suffered a missed miscarriage and had older children aged seven-years-old and 11-months-old:

We will never know what ultimately lead to my partner taking his own life, and I do not blame any service or person, but I do believe that - if the system were different, and dads were cared for in the same manner as mums are after the loss of a baby, and throughout the pregnancy and birth process - that outcomes could be changed for many families. A screening process for dad's mental health COULD have flagged up something, COULD have stopped my partner from taking his life and COULD have stopped our loss.

Further reading and references:

[1] Hambridge et al, (2021). ‘”What kind of man gets depressed after having a baby?” Fathers’ experiences of mental health during the perinatal period.’ BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 21:463. [Weblink]

[2] Mayers et al, (2020). ‘Supporting women who develop poor postnatal mental health: what support do fathers receive to support their partner and their own mental health?’ BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 20:359. [Weblink]

[2] Daniels et al, (2020). ‘Be quiet and man up: a qualitative questionnaire study into fathers who witnessed their partner’s birth trauma.’ BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 20:236. [Weblink]

Knapman, (2018). ‘The truth about paternal PND.’ Community Practitioner. 91(3), 37-39. [Weblink]

Mental Health Foundation, (2018). ‘Father’s Day: a focus on young fathers and mental health.’ Mental Health Foundation. [Weblink]

Quevedo et al, (2011). ‘Risk of suicide and mixed episode in men in the postpartum period.’ Journal of Affective Disorders. 132(1-2), 243-246. [Weblink]

WHO (2021). Suicide Worldwide in 2019 – Global Health Estimates. [Weblink]

To receive a copy of Mark Williams’ Fathers Reaching Out – Why Dads Matter report, either in hard copy or electronic format, please email hello@thedadpad.co.uk.